I came across this "Mindful Pouring" (精明的开局) game on WeChat recently, and honestly? It's kind of interesting. The puzzle mechanics are simple but really engaging - you pour colored liquids between tubes to sort them out.

I realized this is a perfect opportunity to apply AI planning techniques to solve it automatically. This turned into a fun little project where I formulated the game as a planning problem.

The Puzzle: Simple Rules, Tricky Solutions

Here's how it works: you've got a bunch of tubes filled with colored liquid blocks stacked on top of each other. Some tubes are full, some are partially filled, and you usually get a couple of empty ones to work with. Your job? Sort all the colors so each tube contains only one color (or is completely empty).

The catch is you can only pour from the top of one tube to another, and only if:

- The destination tube has space (isn't already full)

- Either the destination is empty, OR the top color matches what you're pouring

Sounds easy, right? Try it yourself and you'll quickly realize it's a proper puzzle. You need to think several moves ahead—pour the wrong color at the wrong time and you'll paint yourself into a corner with no way to untangle the mess.

This is exactly the kind of problem AI planning was designed for: we have a clear initial state, well-defined rules about what moves are legal, and a specific goal we want to reach. The question is: can we get a computer to figure out the sequence of moves automatically?

Planning Problem Formulation

To solve this with AI planning, I used PDDL (Planning Domain Definition Language) and the Fast Downward planner. Let me first introduce the formal framework, then walk through a concrete example.

A classical planning problem is formally defined as a tuple \(\mathcal{P} = \langle \mathcal{D}, \mathcal{I}, \mathcal{G} \rangle\), where:

- \(\mathcal{D}\) (Domain): Defines the structure of the world

- \(\mathcal{T}\): A set of types (e.g., tubes, colors, levels)

- \(\mathcal{O}\): A set of objects typed by \(\mathcal{T}\)

- \(\mathcal{P}\): A set of predicates that describe properties and relations

- \(\mathcal{A}\): A set of actions, each with parameters, preconditions, and effects

- \(\mathcal{I}\) (Initial State): A set of ground predicates that are true initially

- \(\mathcal{G}\) (Goal): A set of ground predicates that must be satisfied

Each action \(a \in \mathcal{A}\) is defined as:

- Parameters: Typed variables that the action operates on

- Preconditions \(\text{pre}(a)\): Conditions that must hold for the action to be applicable

- Effects \(\text{eff}(a)\): Changes to the state after executing the action

- \(\text{eff}^+(a)\): Predicates that become true (add effects)

- \(\text{eff}^-(a)\): Predicates that become false (delete effects)

A solution is a sequence of actions \(\pi = \langle a_1, a_2, \ldots, a_n \rangle\) that transforms the initial state \(\mathcal{I}\) into a state satisfying the goal \(\mathcal{G}\).

Our Example Puzzle

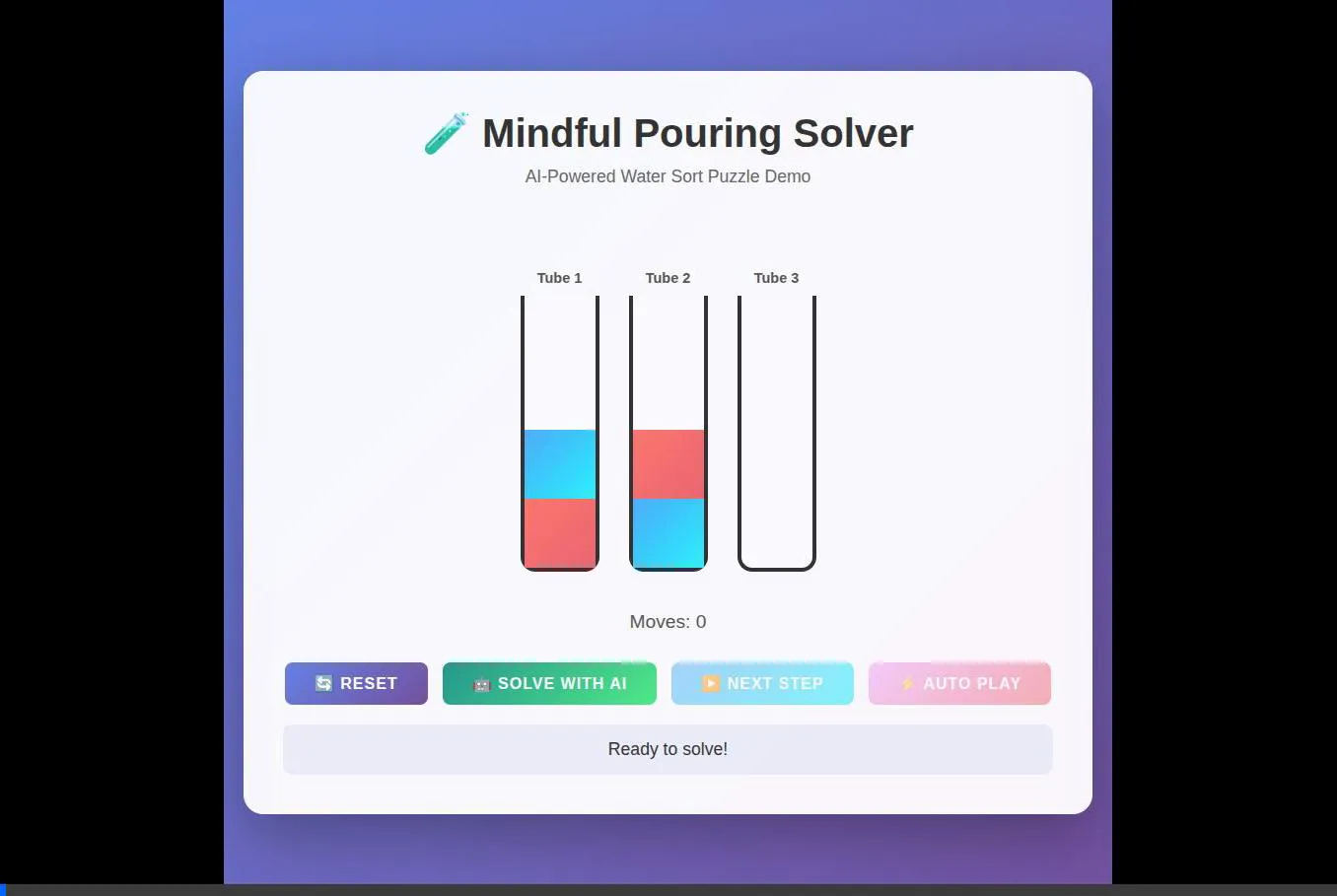

Now let's see how this formal framework applies to our water sort puzzle. Imagine we have 3 tubes, each can hold up to 2 blocks:

Tube 1: [🔴 🔵] (bottom to top)

Tube 2: [🔵 🔴]

Tube 3: [ ] (empty)

Goal: Sort so each tube is either empty or contains only one color

a). Types and Objects (\(\mathcal{T}\), \(\mathcal{O}\))

First, we define the types \(\mathcal{T}\) and objects \(\mathcal{O}\) in our domain. For our example:

- Tubes:

t1, t2, t3 - Colors:

red, blue - Levels:

l0, l1, l2(wherel0is the base, andl1-l2are the two slots)

In PDDL, we declare these with types:

(:objects

t1 t2 t3 - tube

red blue - color

l0 l1 l2 - level

)b). Predicates (\(\mathcal{P}\)) and Initial State (\(\mathcal{I}\))

We need predicates (true/false statements) to describe what's happening in each tube. For our example puzzle, here's how we represent Tube 1 with [🔴 🔵]:

;; Tube 1 contents

(has-color t1 l1 red) ;; Bottom slot has red

(has-color t1 l2 blue) ;; Top slot has blue

(top t1 l2) ;; The topmost filled level is l2For the empty Tube 3, we just mark it as empty:

;; Tube 3 is empty

(top t3 l0) ;; Top pointer at base means emptyWe also need some static facts about the structure (which levels are above others):

;; Level structure (gravity!)

(above l1 l0) (above l2 l1)

(is-base l0)c). Actions (\(\mathcal{A}\))

Our action set \(\mathcal{A}\) contains a single action: \(\texttt{pour}\). This action moves one block from the top of one tube to another. The key is defining the preconditions \(\text{pre}(\texttt{pour})\) and effects \(\text{eff}(\texttt{pour})\) correctly. We can only pour if:

- The source tube has a block at its top

- The destination tube has space

- The destination is either empty OR its top color matches what we're pouring

For example, in our initial state, we could pour the blue block from Tube 1 (top) to Tube 2 (top) because Tube 2's top is also red. Or we could pour it to the empty Tube 3.

Design choice: I chose to pour one block at a time rather than all contiguous blocks of the same color. This makes the PDDL simpler, though the planner might need more steps.

d). Goal State (\(\mathcal{G}\))

Each tube should be either completely empty or completely filled with a single color. For our example with 2 colors and 3 tubes, one valid goal state would be:

Tube 2: [🔵 🔵]

Tube 3: [ ] (empty)

In PDDL, we express this as:

(:goal (and

;; Tube 1 is all red

(has-color t1 l1 red) (has-color t1 l2 red)

;; Tube 2 is all blue

(has-color t2 l1 blue) (has-color t2 l2 blue)

))Putting It All Together

With these components defined, we have our complete planning problem \(\mathcal{P} = \langle \mathcal{D}, \mathcal{I}, \mathcal{G} \rangle\). Fast Downward can now search for a solution \(\pi = \langle a_1, a_2, \ldots, a_n \rangle\) — a sequence of \(\texttt{pour}\) actions that transforms our initial state into a goal state.

The planner uses heuristics (like the \(h^{\text{add}}\) or \(h^{\text{FF}}\) heuristics) to guide the search efficiently, avoiding the need to explore every possible state. For our simple example, the solution is quite short, but the same approach scales to much more complex puzzles!

So... Does It Actually Work?

The solver in action - watch it automatically solve the puzzle step by step

Yes! With Fast Downward, we can solve these puzzles optimally. The planner explores the state space systematically, using heuristics to guide the search. What takes humans 20 minutes of frustrated tapping can be solved in seconds.

The beauty of this approach is its generality. Once you've defined the domain, you can throw any puzzle configuration at it and the planner figures it out. Check out the interactive demo if you want to try it yourself!

Now, is this overkill for a mobile game? Absolutely. But research is supposed to be fun, right? Don't take it too seriously—let's just have fun! 🎮

But seriously... is this useful? Maybe. Think about it: humans learn strategies by playing these games. We practice our minds, think deeper each time, develop intuitions about valid moves without exhaustively searching to the end. We build mental models of how liquids pour, how colors stack, what moves lead to dead ends.

Large language models struggle with this kind of reasoning. They can't easily "see" the causal structure of pouring, can't mentally simulate the physics, can't plan multiple steps ahead in visual-spatial tasks. Could puzzles like this be a key to enhancing visual reasoning in VLMs? Could training on such tasks improve their understanding of real-world physical interactions?

It's worth thinking about. Sometimes the best research questions come from the most playful explorations. Maybe there's something here about grounding abstract reasoning in concrete, interactive tasks. Or maybe I just wanted an excuse to avoid playing level 3. Either way, it was fun to explore! 🤔